The Aspartame Saga

September 20, 2023

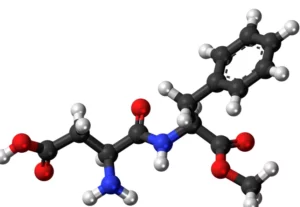

A division of the World Health Organization (WHO) declared in July that aspartame possibly causes cancer. In making that announcement the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) started a shouting match among experts and other agencies. Is aspartame, the sweetener present in so many diet sodas and other foods, really dangerous to human health?

In fact, a different group within the WHO, the Joint Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA), takes a completely different position, insisting that aspartame is safe for human consumption. And the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) agrees with that assessment. As we have pointed out many times before, nutrition and diet sciences are plagued by conflicting findings and guidelines that seem to change daily. The result is that people are confused. No one wants to ingest a carcinogenic substance, but millions of people have been consuming aspartame for decades. People will have one of two reactions to the conflicting pronouncements about aspartame: some will be frightened and try to avoid all food and drinks containing aspartame, while others will decide to ignore the warning about aspartame entirely, perhaps convinced that no one really knows for sure what is safe for us to eat and drink.

The Evidence is Limited

Several commentators have tried to make sense of why the IARC warning about aspartame is so controversial. To begin with let’s remember why aspartame is such a popular food additive. It is about 200 times sweeter than sugar, so tiny amounts make food and beverages taste sweet without the calories of sugar. That creates the impression that we can control our weight or even lose weight if we imbibe diet soda instead of sugar-sweetened drinks. We’ll comment on that impression, which itself is controversial, a bit later. We can agree for now that substituting high-calorie foods for aspartame-sweetened foods is not advisable.

Paul D. Terry, a Professor of Epidemiology, Jiangang Chen, Associate Professor of Public Health, and Ling Zhao, Professor of Nutrition, all at the University of Tennessee, tried to make sense of the aspartame saga in a piece in The Conversation. They explain that the IARC specifically pointed to a handful of animal and human studies that found a link between aspartame use and hepatocellular cancer, a type of liver cancer. But the committee put aspartame in carcinogen category 2b, meaning that the evidence to support an adverse effect is “limited.” And the IARC acknowledged that many extraneous factors could account for the potential link between aspartame and liver cancer, including chance and the fact that aspartame-containing products may be preferentially consumed by people with diseases that increase their risk for cancer. They also acknowledged what we have pointed to before: it is extremely hard to study people’s dietary habits and know precisely what they are eating and drinking. Most things in diet science rely on peoples’ self-reports and these can be inaccurate. It is very hard to expect people to record exactly what and how much they eat and drink over the prolonged periods of time necessary to find out if something causes cancer.

The IARC advisory doesn’t say anything about how much aspartame one would have to consume to be at risk for cancer and that is a problem because we know that most carcinogenic substances operate on what is called a “dose-response” curve, with higher doses, longer exposures, and doses above a certain threshold more likely to be problematic. After all, you don’t get lung cancer if you smoke one cigarette a year or skin cancer if you are exposed to sunlight for a few seconds once a month. The other WHO committee involved in this, JEFA, does make a recommendation for the maximum amount of aspartame one should consume in a day: about 40 milligrams per kilogram of body weight. That translates into approximately 8 to 12 cans of diet soda. And the FDA is even more lenient, recommending an upper limit of 50 milligrams per kilogram of body weight per day. It is fair to say that most people consume well below that amount.

Christine Jewel in the New York Times reviewed the studies that IARC relied on to make its decision. One set of studies involved feeding aspartame to rodents to see if there is an increase in tumors. While such studies can suggest a link, however, it is well known that many things cause cancer in mice and rats that do not do so in humans. Furthermore, Jewel writes, “The F.D.A. has dismissed the long-debated studies as ‘compromised.’” The IARC group considered three human studies, one led by WHO officials, one by a consortium of researchers from Harvard, Boston University, and the National Cancer Institute, and one by the American Cancer Society. All three studies do show an elevated risk of liver cancer in people who drink much less than a dozen cans of aspartame-sweetened beverages a day.

Some Studies are Reassuring

According to epidemiologist Gideon Meyerowitz-Katz, writing in STAT: “…there have been quite a few studies looking at aspartame and other artificial sweeteners over the years. Generally, they have overwhelmingly been quite reassuring about the potential for cancer risk.” Meyerowitz-Katz goes on to review a number of those studies and points out that even when a study did find an association between cancer and aspartame, aspartame “increased the risk of cancer by 0.2%,” a very small risk indeed. He also points out that the alternative to artificial sweeteners—sugar—itself carries cancer risks. “And that’s why I’m personally not worried about my Diet Coke/Coke Zero intake,” he concludes. “Yes, there’s some vague evidence that aspartame may be associated with an increased risk of cancer. There’s also some evidence it isn’t! But even the evidence suggesting that it might be shows a risk so low that it’s unlikely to mean much to my life.”

While that conclusion may be reassuring to many, it still leaves on the table the fact that some studies have found an association between aspartame and cancer and one respected agency, IARC, calls aspartame a possible carcinogen. There is no easy answer here. No one will say to us “there is absolutely nothing to worry about, drink as much diet soda, up to the recommended maximum, as you wish.” What they all say is that the evidence for an association is limited, that the risk if it exists is very small, that you will probably be okay if you drink small amounts of diet soda. And those words tap into the vagaries of individual tolerance for risk. On the one hand, it would be perfectly reasonable to say, “no one needs to drink diet soda to stay alive, so why accept any risk at all. I’m going to cut it out completely.” On the other hand, it would be equally reasonable to say, “after reading everything that is known about this aspartame-cancer connection, I conclude that even if there is a risk it is very small and I can stay safe by drinking less than 12 cans of diet soda a day, just as the FDA recommends.”

Diet Soda May Not Cause Weight Loss

Another important thing to remember in deciding whether to consume products that contain aspartame is that there is actually no solid evidence that they are associated with weight loss. One reason they may not has to do with human physiology. When we consume food and beverages that contain sugar there is an increase in our blood level of glucose and this is detected by a part of the brain called the hypothalamus, which then sends a signal to the pancreas to produce more insulin to lower the blood glucose level. When we consume food and beverages that contain aspartame, however, the hypothalamus is tricked into thinking there is more glucose around, sends that same signal, and blood glucose levels are reduced even though in fact there has been no increase in glucose. And that decrease in blood glucose can make a person feel hungry and crave sugar-laden products to compensate. Thus, it is even possible that regularly consuming aspartame-containing foods and beverages can lead to some people gaining weight.

Of course, to be completely safe, one could substitute water for aspartame-containing beverages. Water also has no calories and, assuming you live in a place where the municipal water supply is lead-free and you aren’t too worried about PFAS (“forever chemicals”) in your drinking water, you can consider yourself free of even a “possible” risk for cancer if you drink tap water instead of diet soda. It will be interesting to see if the IARC declaration has any effect at all on diet beverage sales and if any significant number of people switch to drinking water. The evidence that aspartame causes cancer is confusing and the decisions we make will depend on how much risk we feel comfortable taking.

Related Posts

We Need to Maintain Funding for Biomedical Research: Witness CRISPR, CAR-T, and the Dark Genome

Posted in Cancer

We need to maintain federal funding for scientific research. CRISPR, CAR-T, and the Dark Genome are examples of why.

Two Events Affecting Women's Health Challenge Scientific Certainty

Posted in Cancer

Two recent reports related to women's health, one about breast cancer screening guidelines and the other about hormone replacement therapy, showcase how uncertain medicine can be.

Cancer Screening Does Not Always Extend Life

Posted in Cancer

Is cancer screening beneficial? Does it extend life? The evidence might be less clear than you think.